Introduction

Recently I came across a very interesting method to generative modeling that has its foundations in Physics. Naturally I had to dig in. Generative modeling involves learning a probability distribution from the given dataset and using the learned distribution to produce new samples. Over the last few years, the state of the art results in this type of modeling were all produced by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). Recently, a new class of generative models called score-based models have gained attention. As it happens, the main tools of these models come from what is called the Brownian motion - the chaotic motion of a particle (like a pollen) floating on a liquid (like water). In this blog post, I will try to explain the physics principles behind score-based models. First, I will go over the physics and then come back to its connection to score-based models.

Langevin Dynamics

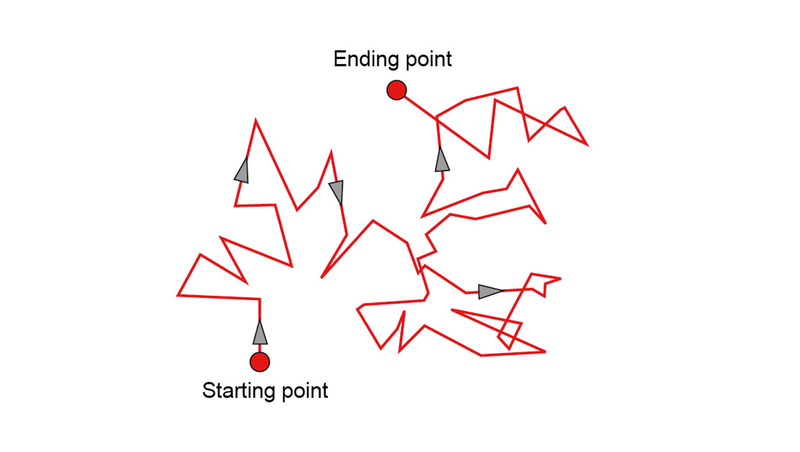

When a particle like a pollen floats on water, it experiences a constant barrage of collisions from the molecules of the water. Occasionally, these collisions are energetic enough to kick the particle in a particular direction. The particle as a result, exhibits a random zig zag motion. This is called the Brownian motion, named after Raboert Brown who first discovered the phenomenon in 1827, while looking through a microscope a pollen immersed in water.

It can be established that the dynamical equation describing the chaotic motion of the particle to be

\begin{equation}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} = - a \nabla U(x) + b\eta(t).

\end{equation}

where the first term describes the friction force on the particle and the second term describes the random fluctuations in the density of the liquid. In fact, \(\eta(t)\) is a white noise term with properties \(\langle \eta (t) \rangle = 0\) and \(\langle \eta (t_1) \eta (t_2) \rangle = b \delta(t_1-t_2)\). One central aspect of this equation is that it only captures a coarse grained state of the liquid as opposed to a fine grained state that precisely takes into account of the motion of all the molecules. In fact, we do not desire such a description as we will have to then specify the exact position and momentum of all the molecules in order to find the motion of the particle. In the above equation, all the random motion of the molecules is abstracted away in the white noise term \(\eta(t)\). The dynamics produced by equation (1) is called the Langevin dynamics.

It is clear that the Langevin dynamics is completely random - two particles with the same initial conditions will exhibit different motion due to the white noise term. In such a situation, it makes sense to consider a very large number of particles and ask what is the concentration of the them as time evolves. In other words, we could ask what is the probability that a particle is at a perticular position and time. This can be worked out and shown that the resulting probability density function \(P(x,t)\) obeys what is called the Fokker-Planck equation

\begin{equation}

\frac{\partial P}{\partial t}(x,t) = a \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\nabla U(x) \hspace{0.1cm} P(x,t)\right) + \frac{b^2}{2}\frac{\partial^2P}{\partial x^2}(x,t).

\end{equation}

Given the Fokker-Planck equation describing the evolution of the particles, a natural question to ask is what is the steady state solution? First, should there even be a steady state solution? The second question is simple to answer as after enough time, the particle will have interacted with enough number of molecules of the liquid to come to a steady state. This doesn’t mean that the particle has come to rest. It just means that transitory effects due to the initial conditions will have died down and as a result the function \(P(x,t)\) becomes independent of the time variable. Plugging \(P(x,t) = P_s(x)\) in equation (1), we get

\begin{equation}

\frac{\partial }{\partial x}\left[ a \nabla U\hspace{0.1cm} P_s + \frac{b^2}{2}\frac{\partial P_s}{\partial x} \right] = 0.

\end{equation}

This equation can be solved with the trivial boundary conditions \(P_s(x=\infty) = 0\) and \(\frac{\partial P_s}{\partial x}(x=\infty) = 0\). The resulting solution is

\begin{equation}

P_s(x) = \frac{1}{Z}exp\left( - \frac{2a}{b^2} U(x) \right),

\end{equation}

where \(Z\) is the normalizing constant.

To summarize, I started with the equation describing Langevin dynamics, then showed the Fokker-Planck equation and solved for its steady state solution. The most important point I would like to emphasize again is that equation (1) that describes Langevin dynamics doesn’t capture all the information about the motion of the molecules of the liquid. Only the coarse grained information of the molecules’ motion is represented in equation (1) through \(\eta(t)\). Due to this loss of information, the only meaningful way to talk about the particle motion is using the probability density function \(P(x,t)\). This should be contrasted with other systems, for example, motion of a ball in vacuum. Here everything is deterministic and therefore we do not need any probability function to describe the motion of the ball.

This is all the physics that we will need. I will end this section by making a few observations that will be useful later. First, notice that the gradient of \(log P_s(x)\) is

\begin{equation}

\nabla log P_s(x) = -\frac{2a}{b^2}\nabla U(x),

\end{equation}

where we have used the fact that \(Z\) is a constant. Another equation that will be useful for us later is the discretized version of equation (1):

\begin{equation}

x_{i+1} - x_i = -a \nabla U(x_i) \epsilon + b \sqrt\epsilon \hspace{0.1cm}\tilde \eta

\end{equation}

where \(\epsilon\) is a small time step and \(\tilde\eta\) is sampled from normal distribution.

Score-based Generative Modeling

The main idea in Generative modeling is to learn the probability distribution of the data and use it to generate new samples. One recurring and intractable problem in generative modeling is normalizing the learned probability function

\begin{equation}

\int p_{\theta}(x)dx = 1,

\end{equation}

as it involves integrating over a very high dimensional space. One way to circumvent this problem is to use the gradient of the log probability function as

\begin{equation}

\nabla log\left( c \hspace{0.1cm}p(x)\right) = \nabla log\left(p(x)\right),

\end{equation}

where \(c\) is a constant. So how do we learn the gradient of the log probability? This is done using what is called score-matching. One starts with an objective of minimizing the Fischer divergence defined as

\begin{equation}

E_{p(x)}\left[ ||\nabla log(p(x)) - s_{\theta}(x)||^2_2\right],

\end{equation}

to learn \(\nabla log(p(x))\). This might seem like a chicken and egg situation since we would also need to know \(p(x)\) to evaluate the Fischer divergence. Fortunately, there exists a set of methods called score-matching that obviates the need of knowing \(p(x)\). To proceed further, let us assume that we have learnt the gradient of the log probability.

Now, the next problem is how do we use \(\nabla log(p(x))\) to generate samples. This is where the Langevin dynamics come in. We can identify (the still unknown) \(p(x)\) with the steady state solution of the Fokker-Planck equation \(P_s(x)\). Then we know how to generate samples for \(p(x)\) using only the knowledge of its gradients. We just need to use equation (6)

\begin{equation}

x_{i+1} = x_i + \frac{2}{b^2} \nabla log(p(x)) \epsilon + b \sqrt\epsilon \hspace{0.1cm}\tilde \eta \hspace{1cm} i = 0,1,2,…,N,\hspace{.1cm} with\hspace{.1cm} N\rightarrow \infty

\end{equation}

repeatedly for a large number of times starting with random initial conditions. By Fokker-Planck equation, we are assured that the final positions \(x_N\) (\(N\) being very large) will tend to be the samples generated by the probability density function \(p(x)\).

Conclusion

I started with the equation describing Langevin dynamics, exhibited Fokker-Planck equation and its steady state solution. I then moved on to score-based generative modeling where we learn the gradient of the log probability rather than the distribution itself. This way we avoid the problem of probability normalization. Once we have learnt the gradients we can use the discretized Langevin dynamics to sample from the distribution. It is quite amazing how the equations describing the physics of Brownian motion ends up providing a tool for generative modeling.

The above ideas are closely related to hierarchial variational autoencoders and diffusion models. These models have been recently shown to produce results as good as GANs. I will later on in a separate blog post, elaborate on the connection to these models and possibly also provide a code walk through implementing some of the ideas presented here.

References

- Yang Song’s blog post “Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution”

- Lecture notes 1,2,3 by Prof. Davide Marenduzzo, The University of Edinburgh

- Lecture on “Langevin dynamics for sampling and global optimization” by Kirill Neklyudov